This is the sort of fairy tale I grew up with in the forties and fifties. I didn’t have many books, and those I owned had very few pictures. This wasn’t such a bad thing as you might imagine, because when I heard a story, the whole thing took place in my mind. Cinderella was poor and ragged. Her sisters were horrid to her, her father a distant figure, her step-mother demanding and unkind.

Modern films and illustrations often make Cinderella so glamorous, and there’s never a raggy and grubby old dress in sight. Even the old-fashioned picture on the left doesn’t do justice to the poor girl’s situation. Perhaps because of my upbringing, I still prefer the ordinary-looking girl I imagined all those years ago. To someone like me, a little girl whose mother had to chop wood to get the fire going in the range on a winter’s morning, who had to fetch water from a tap in the road near our cottage, I can easily empathise with the hardship of the story-girl’s life.

And how amazing and romantic her story seemed. I pictured her singing to the mice that scurried about as she scrubbed and polished. I imagined her as never shrieking at her horrible sisters, but bearing her situation with fortitude. I wanted to be just like her. I was not, of course.

Could anyone real be kind and caring when treated as harshly as our heroine?

Children still love fairy tales, yes, but what I learnt as I looked back at Cinderella and other ‘Rags to Riches’ stories, is that there is something in them that encourages us to be our own person, to strive against injustice and unkindness.

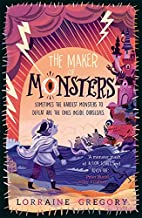

Some of my favourite modern children’s books are ones where the heroes have to fight something or someone much bigger than themselves. They battle against the odds and they win through in the end.

I reckon children will never tire of stories like Lorraine Gregory’s ‘The Maker of Monsters, where we meet Brat, poor, overworked, and alone. Like Cinders he meets his challenges with courage and fortitude.

A hero who finds riches in friendship and kindness. Perhaps the best kind of riches we ever need.